What Wars? What Roses?

The Wars of the Roses never happened – or certainly not in the way Henry VII’s propaganda told it. Even the roses are an invention. Which is why we ask What wars? What roses? But the real question is, what on earth was going on in fifteenth century England? Or, more seriously, could this really have been the end of medieval England and the start of the modern? Well, the intriguing thing is, that when you peep over the edge of the fifteenth century, you discover that something very profound did in fact change.

Why do we know so little about medieval history? About England and Wales in the fifteenth century? The Wars of the Roses (Lancaster v York) lasted 4 months not the traditional 85 years. Even the roses were (mostly) inventions. And was it even medieval? The execution of the King’s chief minister as a traitor in 1450, by sailors dissatisfied with an ineffective king, was shocking. It revealed that the common people believed the true crown was the community. You can’t get more modern than that.

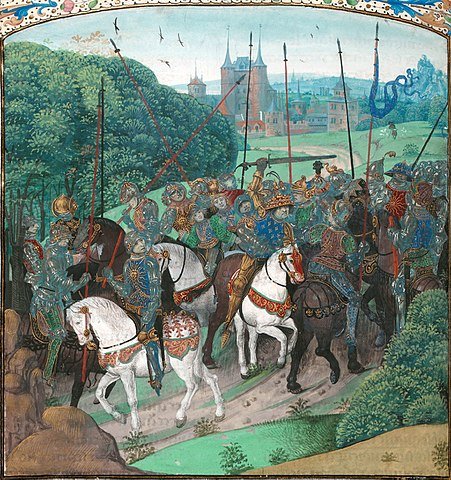

Why was the 15th century in England and Wales so violent? It certainly wasn’t York v Lancaster, white-rose v red-rose rivalry. Monarchs were useless but that’s not unique to the 15th century. So what was it that defined this period? It has everything to do with the plague…

By the time Henry VI finally lost the last bit of England's French Empire in 1453 he could no longer go to war in France to occupy and enrich his nobility. This small, interrelated and bickering group, cooped up in England with an agricultural depression settling in, now resorted to what the historian Michael Postan long ago (in 1939) famously called ‘political gangsterdom.’

One common-girl-denies-king-until-he-marries-her, two kings, three royal murders in the Tower, and the Queen's mother accused of witchcraft. Just about standard for late 15th Century England and Wales.

Henry VII invented the idea of the Wars of the Roses and the notion that he alone could end them. With a comparatively weak claim to the throne he found a novel way to deal with the nobility - through extortioners and hatchet men. He could only get away with this because the Black Death had fatally damaged the status of the nobility and caused the rise of the small independent farmer. Feudalism in England and Wales was over… or at least we thought it was, until now.

Once you begin to read for yourself you’ll appreciate that we have only offered a sketchy taster to this absorbing period. If we’ve given you some ideas to start out with, that will have been a success. But there’s a vast deal more to know.

The best short introduction to the Wars of the Roses still seems to be A.J. Pollard’s The Wars of the Roses (1988) If you want to read something in more detail, then Christine Carpenter’s The Wars of the Roses (1997) is thoughtful and helpful and relatively easy to read. If it’s eyewitness accounts you want, then try JR Lander’s The Wars of the Roses (1965, republished 2007). There are entertaining stories of soldiering scattered about in Anthony Goodman’s The Wars of the Roses (2006) though you need to know the subject before you start or you’ll soon get confused. To dig deeper, try any of the essays in The Wars of the Roses (1995) edited by AJ Pollard.

Let’s just say that historians of the fifteenth century are better at writing books than choosing titles.

The most recent big book on the subject is (all together now) The Wars of the Roses (2010) by Michael Hicks. Hicks, however, has a point to prove, which is that Henry VI was not as hopeless as everyone else thinks, and that the problem was mostly caused by Richard Duke of York. Even Hicks sometimes finds it hard to keep the argument going. Dip into it alongside John Watts Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship (1996) and Lauren Johnson’s Shadow King: the Life and Death of Henry VI (London 2019) and make your own mind up. You will also need to go back to Ralph Griffith’s venerable but still valuable The Reign of King Henry VI (Berkeley 1981), and Bertram Wolffe’s equally ancient and scholarly Henry VI (Yale 1981, new edition 2001).

Gordon McKelvie’s Bastard Feudalism, English Society and the Law (2020) takes you into the changing nature of the nobility and its relationship with wider society, which you’ll have gathered from our discussions we consider the key to the period. These strands are pursued also in Clair Valente, The Theory and Practice of Revolt in Medieval England (Taylor and Francis, Abingdon and NY, 2003), in Gerald Harriss, Shaping the Nation (Oxford 2005) and Stephen Payling’s revealing, ‘Social mobility, demographic change, and landed society in late Medieval England’, Economic History Review 45 (1992), pp. 51-73. TB Pugh’s ‘The magnates, knights and gentry, in SB Chrimes and others (eds), Fifteenth Century England 1399-1509 (Manchester 1972) is still worth a read. For the Earl of Warwick in particular, there’s Michael Hicks, Warwick the Kingmaker (2007). See also Terry Breverton, Jasper Tudor (2014).

Colin Platt’s King Death. The Black Death and its aftermath in late-medieval England (London 1996) is always illuminating, and nowhere more so than on the changing role of the gentry in the era of the plagues. Mark Bailey, After the Black Death: Economy, Society, and the Law in Fourteenth-Century England (Oxford 2021) takes the story still deeper into English society, as does Gwilym Dodd, ‘County and Community in Medieval England’, EHR 134 (2019), pp. 777-820. It was a field C. Davies long ago opened up in his essay ‘Political Society and the growth of government in late medieval England’, Past and Present 138 (1993), pp. 28-57. To get back to the start of this thread, look on archive.org for Kenneth McFarlane’s venerable The Nobility of Late Medieval England (Oxford 1973).

Thomas Penn’s The Brothers York. An English Tragedy (London 2019) is a wonderfully readable and yet scholarly account of the break-up of the Yorkist monarchy 1461-85. Penn’s Winter King. the Dawn of Tudor England (London 2011) continues the story to 1509 with the same exhilarating clarity. For revealing changes in contemporary attitudes to throwing useless monarchs out, read William Huse Dunham jr and Charles T Wood, ‘The Right to Rule in England: depositions and the kingdom’s authority 1327-1485’, American Historical Review 81 (1976), pp. 738-61.

John Watts (ed.), The End of the Middle Ages? (1998) has an excellent essay by RH Britnell on economy and government from the 1450s. Britnell has another essay in Pollard’s 1995 Wars of the Roses. It’s a theme also taken up by WM Ormrod, ‘England in the Middle Ages’ in Richard Bonney (ed.), The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe c. 1200-1815 (Oxford 1999), a volume that retails at a cool £230 (raising yet again the question about what academic publishers imagine books are for).

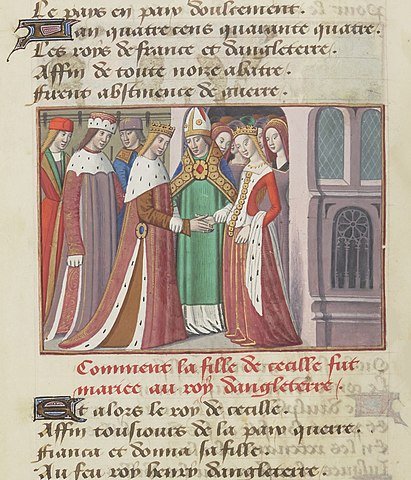

Robert Frame’s ‘Kingdoms and dominions at peace and war’ in Ralph Griffiths, The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (Oxford 2003), pp 149-80 considers the costs of losing English lands in France. But don’t miss Kenneth McFarlane’s essay on the two soldiers, Thomas Winter and Nicholas Molyneux, which is buried away in his essay ‘A business partnership in war and administration,’ English Historical Review 78 (1963). CT Allmand’s ‘The Lancastrian Land Settlement in Normandy 1417-50’, Economic History Review 21 (1968) is also still worth checking out.

For broader contexts check Linda Clark (ed.), The Fifteenth Century XIII; Exploring the Evidence: Commemoration, Administration and the Economy (Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge, 2014) You shouldn’t miss, for example, Matthew Ward’s revealing research on church monuments is in his essay, ‘The livery collar: politics and identity during the fifteenth century’ which is pp. 41-62. For documents with good introductions try Keith Dockray’s Henry VI and the Wars of the Roses. A sourcebook (2000). Michael Jones’s Bosworth 1485 (2002) changed everyone’s understanding of the battle.

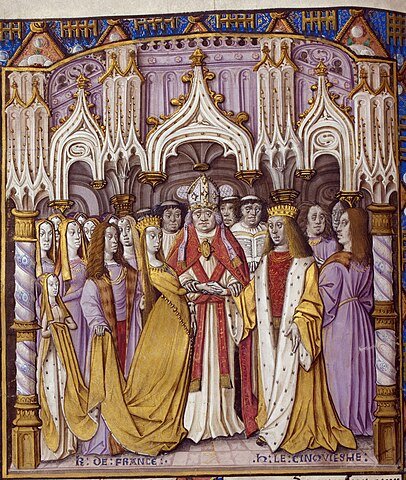

Margaret of Anjou is central to this story. For a balanced account read Patricia-Ann Lee, ‘Reflection of Power: Margaret of Anjou and the dark side of queenship’, in Renaissance Quarterly (1986), pp. 183-217. Helen Mauer’s Margaret of Anjou: queenship and power in late medieval England (Woodbridge, 2003) is perhaps a necessary feminist corrective to older views. It is, sadly, a confusing and less than convincing read, straining to push a modern discourse onto a period it doesn’t fit. Yes, Anjou has had a bad press. But it doesn’t help to argue that it’s exclusively a product of male chauvinism and Yorkist propaganda.

There’s been a fashion for writing about other women in this period. Try Michael Hicks’s Anne Neville (2006), David Baldwin’s Elizabeth Woodville (2002) or Elizabeth Norton’s Margaret Beaufort (2010). Also Henry VI, Margaret of Anjou and the Wars of the Roses by Keith Dockray (2000) and Amy Licence’s readable books on Cecily Neville (Richard of York’s wife), Anne Neville and Elizabeth of York (all 2014).

Thomas Penn’s BBC Winter King (2013) is a workmanlike TV version of his book.

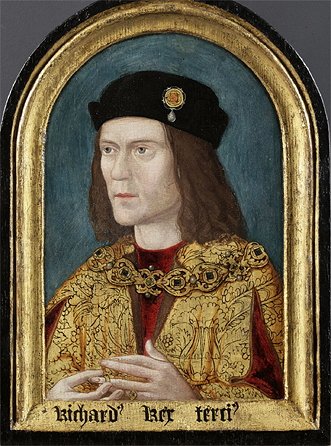

Pretty much all online sites are old-fashioned, saying that it was a long-running feud between York and Lancaster, or it was a long civil war provoked by ‘over-mighty subjects.’ But you should certainly look here and see what the Richard III Society have to say. This is also a great site on the battle of 1461.