The Real-Life Magisterium: the secret history of the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Emperor ‘Constantine’s attempt to ally Empire and Church corrupted the church from what was absoluta et simplex – plain and simple – to a gross caricature’ - 4th Century historian, Ammianus Marcellinus

‘Even wild beasts are less savage to men than Christians are to each other’ - Emperor Julian early AD360s

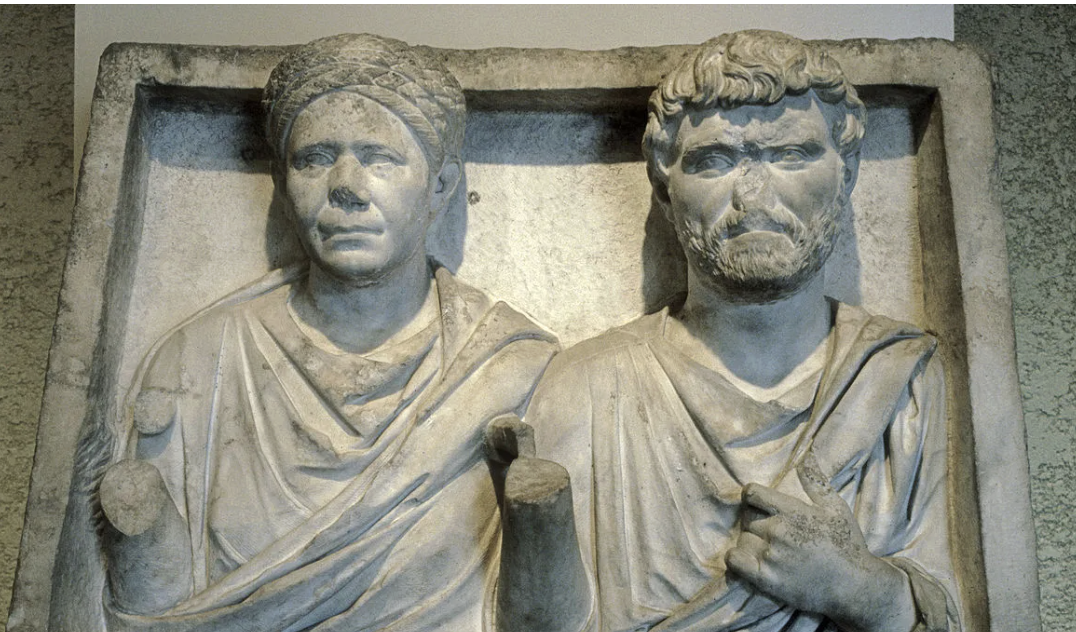

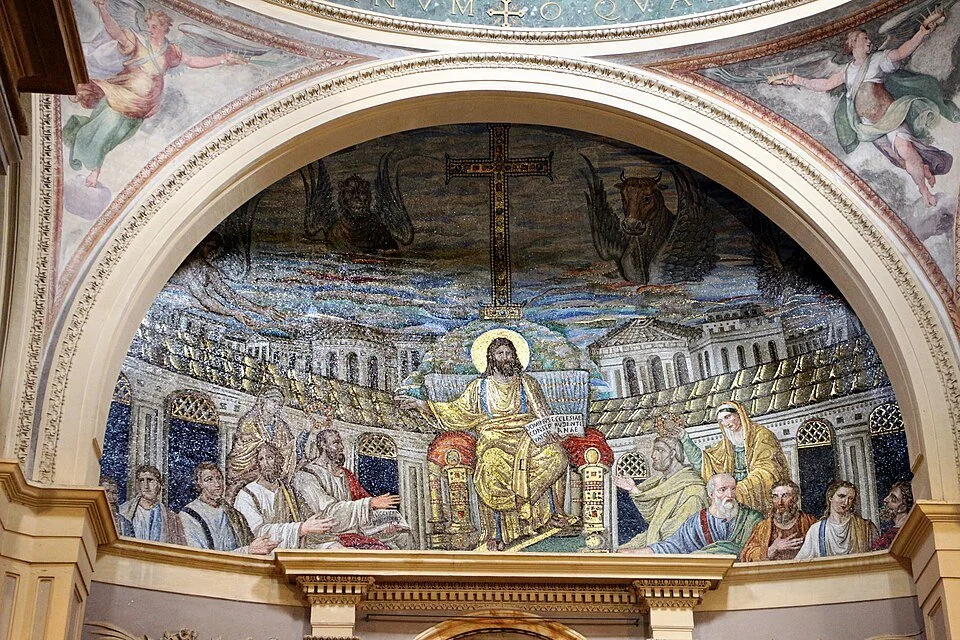

What we have today is a Church completely reinvented in the 4th Century. It had lost virtually all memory of Jesus’s first Apostles. It still uses its invented ‘historical’ genealogies of bishops of Rome (from St Peter to Leo), to shore up its authority. The reality is much more shocking.

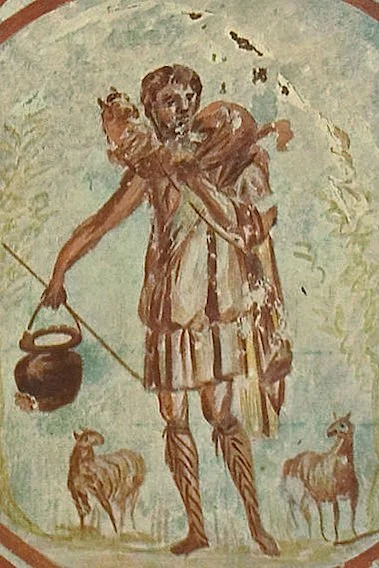

The Church says that Simon Peter was chosen by Jesus as the foundation of the Church. It says that Saint Peter was the first bishop of Rome and that there is a chain of direct continuity from Peter to the present pope Leo. It’s these direct links that gives the Church the right to tell its followers what to do and what to think. But is there any historical evidence?

What real connection is there between the earliest, informal meetings of the first apostles and their friends, and the mighty, glitzy, authoritarian institution that mushroomed in the 4th Century, and especially after AD320? And is still here today. Is it possible that there is in reality, no direct connection at all?

What happened to the women? Until the late second century committed, educated women and men who perhaps space in their own homes led informal house churches. But once church leadership became a paid, public role, they were taken by the men. This was not theology. It was the way of the world.

Chariot races in church. How did we get there? 3rd Century climate change.

By AD400 all it took to be bishop was to be stratospherically wealthy. There was no demand that bishops even knew their bible until AD787.

Church Father, Jerome, wrote this about women who took vows of chastity for God. ‘When she wishes to serve Christ more than the world, then she will cease to be a woman, and will be called a man.’ What now survives from the Roman Empire – and the Church in particular - only tells one, heavily redacted, medieval version of the past.

If you want two mind-bendingly vast subjects, you could choose the early Church and the late Roman Empire. So of course we have only threaded a narrow course. But here is an outline of our research and some essential starting points if you want to dig deeper.

Two books stand out to the modern historian for their breadth and forensic grip on the evidence. Harold Drake, Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000) takes us in detail through Constantine’s supposed conversion and his attempt to turn the church into an organ of the state. Drake develops his thesis in his (much shorter) chapter, ‘The Impact of Constantine on Christianity’, in Noel Lenski’s helpful Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine (Cambridge, CUP 2007).

Kyle Harper, The Fate of Rome, Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (Princetown University, 2017) provides the basic elements of the long durée and unlocks a much clearer understanding of the changing nature of the Empire. I have the impression that many late Roman historians, comfortable with their literary sources, are reluctant converts to this bigger picture. It’s a great and exceptionally revealing read.

You can similarly find a refreshing re-examination of the early church in Keith Hopkins, ‘Christian number and its implications’, Journal of Early Christian Studies, 6 (1998) pp. 185–226. Hopkins is playing a game with mathematical modelling. But his central findings are provocative - that there were very few Christians at first and, of them, only a tiny proportion were literate.

Now read Ramsay MacMullen, The Second Church: Popular Christianity AD 200-400 (Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta GA 2009). It is virtually the only examination of the Christianity of the mass of people, based particularly on the archaeology. MacMullen’s finding, that the wealthy, Latin-reading, ‘Saints’ & ’Church-Fathers’ church was only ever a tiny minority, should be pinned over every Patristic scholar’s desk.

Put alongside these Norman Russell Underwood, ‘The professionalization of the Clergy in Late Antiquity’ (unpublished PhD thesis University of Berkeley, California 2018). Underwood blows a blast of common sense through the often-fevered rhetoric over the evolution of the clergy. As Underwood shows, if you want to study a profession, you have to do prosopography. Once you know who you’re dealing with everything becomes much clearer.

Getting down to more detail, since we’re talking about the emergence of the clergy, add to Underwood, Georg Schöllgen’s excellent analysis of the fluid early Church, ‘The Institutionalisation of Church Ministry in the Second and Third Centuries’ in Alberto Melloni, Federico Ruozzi (eds), Episcopal Elections in the Churches. Laws, Practices, Doctrines. (Bologna Studies in Religious History, Volume 2, Leiden 2025) pp.15-28. Schöllgen puts the key transformation to a professional clergy around AD200. In the light of Underwood, Kyle and the others we list below, we’d go for a date later in the 3rd century.

John Behr’s chapter, ‘Social and historical setting’ in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres, Andrew Louth (eds), Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature (Cambridge, CUP 2004) is also an excellent survey of the lack of structure in the early church, including the disappearance of apostles and the early dominance of women.

Daniëlle Slootjes, ‘Bishops and Their Position of Power in the Late Third Century CE: The Cases of Gregory Thaumaturgus and Paul of Samosata’, Journal of Late Antiquity 4, (2011), pp. 100-115, further examines the way the mid-3rd century crisis opened the way for bishops to acquire civil status, and the church to acquire buildings.

Claudia Rapp takes a more sympathetic view of the early bishops in her Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity: the nature of Christian leadership in the age of transition (University of California 2005). But Rapp doesn’t differ significantly from our view that the bishops simply merged with civil society.

Alistair C Stewart, The Original Bishops. Office and order in the first Christian Communities (Baker Academic, Grand Rapids MI 2014) is an eccentric and sometime exasperating book, apparently little regarded by classical historians. But Stewart gets to the basics of what bishops actually were: for a very long time largely financial administrators.

You can find Anna Leone’s research on North African bishops, which we talk about in the series, in Anna Leone, ‘The Case of Late Roman and Byzantine North Africa’ Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 65/66 (2011-2012), pp. 5-27.

If you still have any doubts about the true character of the early bishops, read Johannes Hahn, ‘The Challenge of Religious Violence Imperial Ideology and Policy in the Fourth Century’ in Johannes Wienand (ed.), Contested Monarchy. Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD (Oxford, OUP 2015). Hahn gives a breathtaking account of violence at the bishops’ hands from the 4th century. Add to it the extraordinary stories of atrocities committed by bishops in Ramsay MacMullen, ‘Cultural and Political Changes in the 4th and 5th Centuries’, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 52 (2003) pp. 465-495. It’s another great piece by MacMullen, who also introduces us to dragons. For yet for more context see Hal Drake’s Violence in Late Antiquity (Routledge, London 2006).

Lauren Kaplow, ‘Religious and Intercommunal Violence in Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries CE’ Hirundo: The McGill Journal of Classical Studies, 4 (2005-2006), pp. 2-26 fills in the broader context of a city ‘notoriously easy to provoke into violence.’ Kaplow argues that the brutality in Alexandria was not only committed by Christians but shows that ‘the Christians provoked the other groups first in all cases.’ See also Christopher Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity (Franz Steiner Stuttgart 2006). This is an important study of a key location, highlighting the extraordinary wealth and power of the church there.

If you imagine St Peter was bishop of Rome, read Michael D Goulder, ‘Did Peter ever go to Rome?’ Scottish Journal of Theology 57 (2004), pp. 377-96 which is a damning summing up of a centuries’ old debate. Add more detail from Brent D Shaw, ‘The Myth of the Neronian Persecution’, The Journal of Roman Studies 105 (2015) pp. 73-100, which shows that the Neronian persecution cannot have happened.

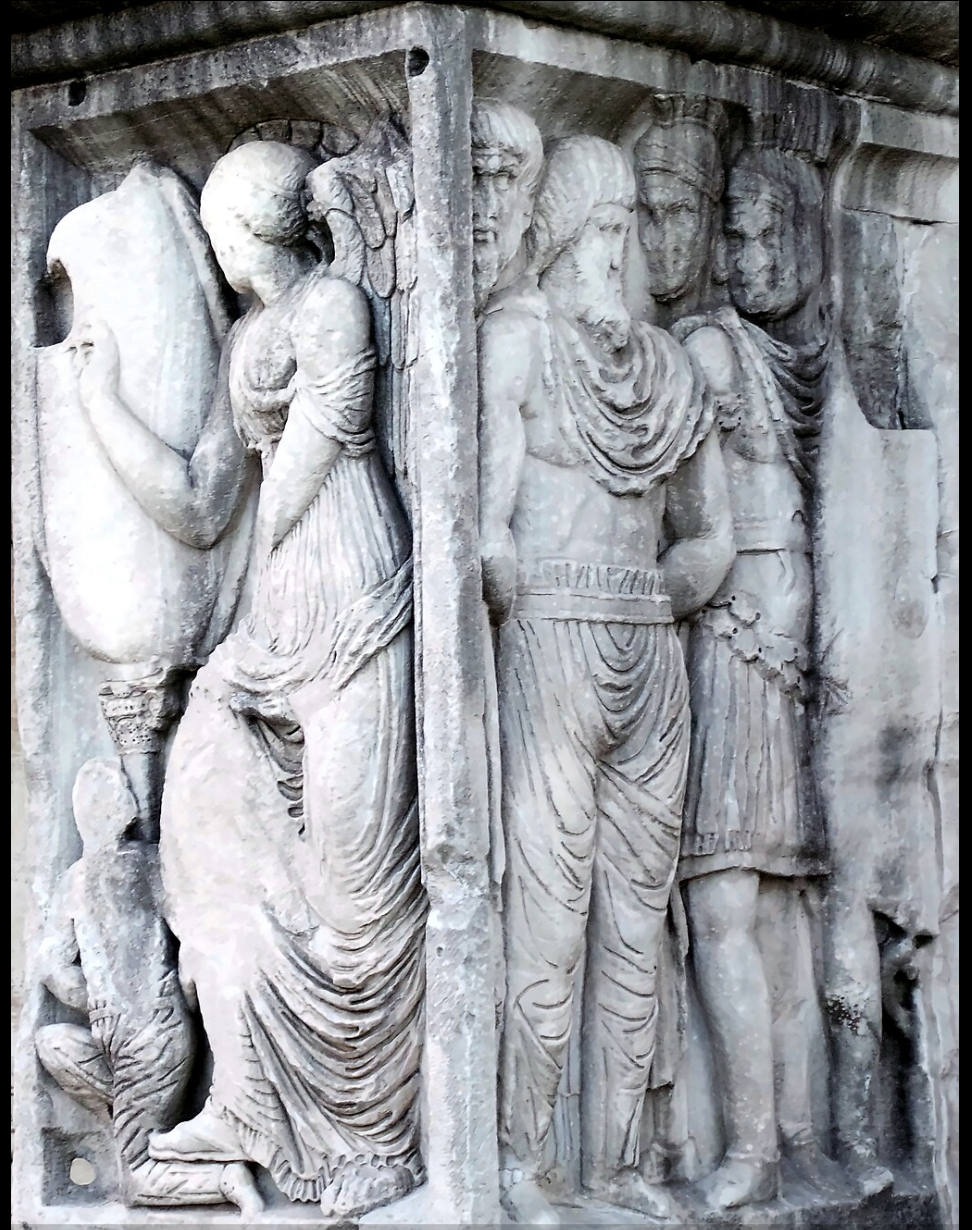

The major work on the Petrine myth is now Roald Dikstra (ed.) The Early Reception and Appropriation of the Apostle Peter (60–800 CE). The Anchors of the Fisherman (Brill, Leiden and Boston, 2020). The contributors tackle vastly more than we can cover in this series. Check out the chapters by Mark Humphries on the Romulus and Remus link, and Annewies van den Hoek on the striking contrast between Latin and Greek inscriptions, and what they tell us about the allegiance of the rich to Peter and the poor to Paul.

George E Demacopoulos, The Invention of Peter: Apostolic Discourse and Papal Authority in Late Antiquity (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) is perhaps careful to keep his options open with the Vatican. But his first chapter ‘Petrine Legends, External Recognition, and the Cult of Peter in Rome’ is a useful review of the emergence of the legends.

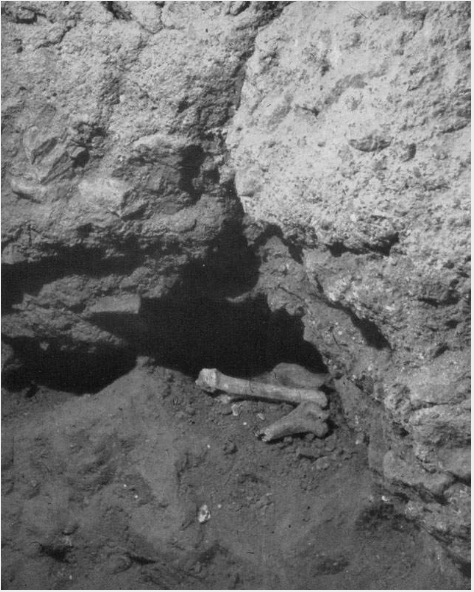

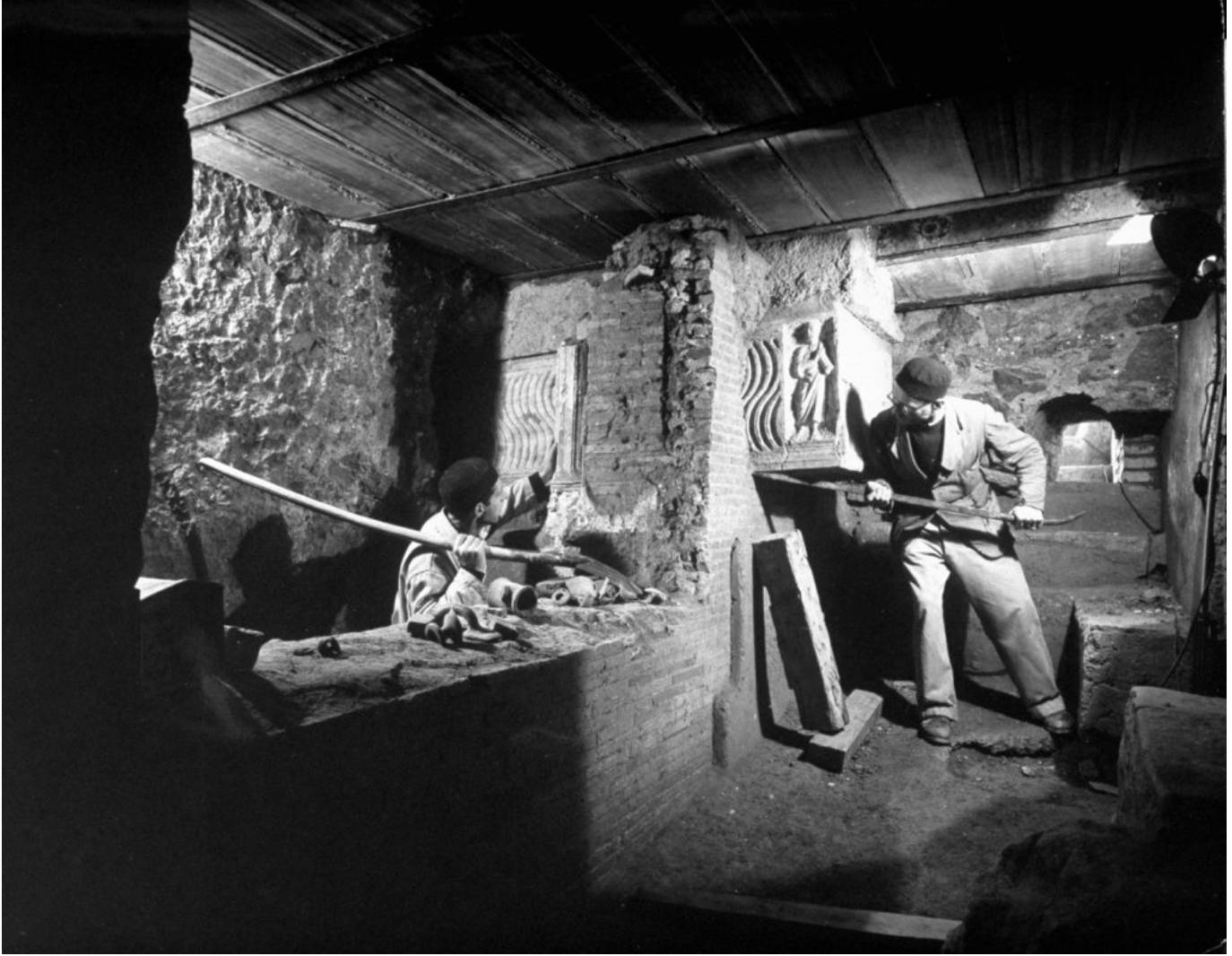

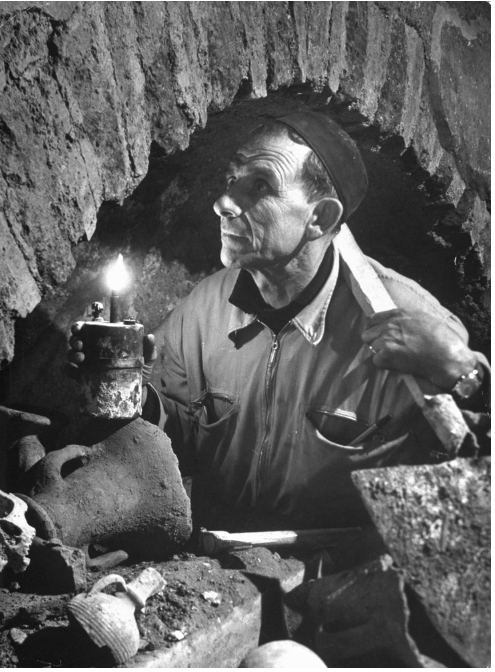

The place to begin with St Peter’s supposed tomb under St Peter’s Basilica is R.R. Holloway, Constantine and Rome (Yale 2004). Chapter 4 is on excavations since Pius XII. You can find the wider context in Paul Baxa, ‘A Pagan Landscape: Pope Pius XI, Fascism, and the Struggle over the Roman Cityscape’ in Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 17 (2006), pp. 107-123. For the background to Ludwig Kaas, see Martin Manke, ‘Ludwig Kaas and the end of the German Center Party’ in H. Beck and LE Jones (eds.), From Weimar to Hitler: Studies in the Dissolution of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of the Third Reich, 1932-1934 (Berghahn Books 2018).

If you want to explore the myth of the Apostolic Succession, read Thomas O’Loughlin, ‘The origins of the idea of “apostolic succession” and its significance for our liturgical practice today,’ in Questions Liturgiques 104 (2024) pp. 155-174. It is a typical piece of O’Loughlin - a common sense demolition of the Apostolic Succession, with thoughts about implications for everyday practice.

You could also try Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, ‘Lists, Originality, and Christian Time: Eusebius’s Historiography of Succession’ in Walter Pohl and Veronika Wieser (eds), Historiography and Identity I: Ancient and Early Christian Narratives of Community (Turnhout, Brepols 2019), pp. 191-217. Johnson examines the lists of ‘bishops’ in the early 4th century writer Eusebius of Caesarea and argues that Eusebius took lists created as polemic and used them as chronology. Which is true but advances the argument less far than Johnson seems to think.

Andrew Louth, ‘Eusebius and the birth of Church history’ in Young, Ayres and Louth, Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature is an excellent introduction to Eusebius. From there, try Robert Markus, The End of Ancient Christianity (Cambridge, CUP 1990) which explores separating clerical culture from folklorique, an idea he borrows from French historian Jacques Le Goff. Markus suggests that Eusebius and his generation were desperate to find continuities with the past. It’s an idea we don’t use, not least because it seems to us that Christians had been looking for similar continuities since at least the fall of Jerusalem. But Markus is right that Eusebius’s solution was to stress the clergy. He goes on to argue that the late 6th was the real break with classical antiquity, in which the educated elite shrank and church grew in importance.

For a writer whom we quote who is slightly later than Eusebius, see John Matthews The Roman Empire of Ammianus (John Hopkins University Press 1989).

For Constantine, read Drake (above). Also Young Richard Kim (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea (CUP 2021) and especially the chapter by Raymond van Dam, ‘Imperial Fathers and Their Sons. Licinius, Constantine, and the Council of Nicaea.’ Van Dam explores the idea (which we can’t go into) that Constantine’s own disputed succession was related to his proposed slogan ‘of one substance with the father’. Drake’s chapter in this book, ‘The elephant in the room’ is also worth reading.

For more evidence of Constantine’s lack of conversion, see Bruno Bleckman’s chapter ‘Constantine, Rome, and the Christians’ in Johannes Wienand (ed.), Contested Monarchy. Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD (OUP 2015)

The best place to start if you want more on heresy is David Gwynn and Susanne Bangert (eds.), Religious Diversity in Late Antiquity (Brill, Leiden and Boston, 2010). Gwyn’s introduction is an enormous bibliography. He shows, among other things, that we struggle to understand Arianism because only his enemies’ writings were permitted to survive.

Michel-Yves Perrin, ‘The limits of the heresiological ethos in late Antiquity’ in the same volume makes the point that difference of belief was believed to be polluting in ancient society. But Perrin also points out that lines between various ‘heresies’ were blurred, and especially in the 4th century. Isabella Sandwell’s chapter, ‘John Chrysostom’s audiences and his accusation of religious laxity’ notes that much religion at the end of the 4th century and early in the 5th was lax, kept up largely for appearance. It’s a necessary reminder that people did not necessarily take religion any more seriously in the past than they do today.

The evolution of liturgy is a complex and related issue. See Anscar J Chipungo (ed.) Handbook for Liturgical Studies volume 1 (Pontifical Liturgical Institute, Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota 1997). The standard text is still Josef A Jungmann, The Early Liturgy to the time of Gregory the Great (University of Freiburg 1959). On the invention of Chrysogonos and Anastasia (who appear in the 4th century Roman rite and haven’t ever left) see Michael Lapidge, The Roman Martyrs, Translations, and Commentary (OUP 2017)

Two more books, finally, on the church. Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom. Triumph and diversity AD200-1000 (Blackwell 1996, Wiley 2013) is a classic by one of the greats of the historiography. Brown argues that the 3rd century crisis is the moment of change, with imperial government becoming more intrusive.

Ilaria Ramelli et al (eds.), T&T Clark handbook of the early church (Bloomsbury, T&T Clark 2022) has much interesting additional material. Mark Edwards, ‘Christianity and Christianities’ is an account of heresies from an author openly attached to authority within the church. The various gymnastics he performs to make his evidence fit his starting point are an entertainment in themselves. Similarly, Nicholas Sagovsky, ‘The Church. One, holy, catholic, apostolic’ shows, rather against the author’s intention, how it was the authoritarian texts that survived (texts that are much more open to interpretation than Sagovsky allows.)

In the same volume Paul van Geest and Bart J Koet, ‘The Christian community and its structure. Deacons, priests and bishops’ adds a further analysis of the rise of hierarchy and the idea of succession. They argue that, from the mid 3rd century the idea began to emerge that ordination inferred some kind of permanent change. See also Ramelli’s own chapter on women leaders, ‘What was the role of women in the churches?’ It is arguably overwritten, and ignores, for example, the problem with terms such as ‘priest’ or ‘bishop.’ But Ramelli brings a large basket of evidence into the debate.

It's well past time to look more generally at the late Rome Empire. Start with Kyle Harper (above). And of course, read anything by Peter Heather or Brian Ward-Perkins.

Then just a few suggestions, particularly about social change.

Wolf Liebeschuetz, ‘Transformation and Decline: Are the Two Really Incompatible?’ in Liebeschuetz, East and West in Late Antiquity. Invasion, Settlement, Ethnogenesis and Conflicts of Religion (Brill, Leiden & Boston 2015) is a piece about the shift in balance of power among the rich from one of the period’s great practitioners.

On the 3rd century crisis use O. Hekster, G. de Kleijn and Daniëlle Slootjes, Crisis and the Roman Empire (Leiden 2007), particularly the essays by Liebeschuetz, Bruun, Jongmann.

Towns are key to the Roman empire. Look at Douglas Underwood, ‘Late Roman cities in the West’, in Miko Flohr and Arjan Zuiderhoek (eds). A Companion to Cities in the Greco-Roman World (Wiley, Hoboken 2025). Also in the same volume, Ine Jacobs, ‘Greco-Roman cities in the Late Antique East’ and (for much context) Luuk de Ligt, ‘Urban patterns in the Early Roman Empire, 27 BCE–250 CE’. Christopher J Dart, ‘Politics and political institutions in Roman cities in Italy and the West’, shows how the old imperial system for the poor was overwhelmed.

Also worth reading in this collection is Sean Kingsley and Michael Decker, ‘New Rome, New Theories on Inter-Regional Exchange. An Introduction to the East Mediterranean Economy in Late Antiquity’. Kingsley and Decker show how the traditional model of rigid hierarchy is no longer tenable. They also show the church quickly becoming an economic force. You might also read Stef Boogers, Bas Neaujean, Jeroen Poblome, ‘Cities as sociological systems in the ancient world.’

Carlos Machado, ‘Looking for the poor in Late Antique Rome’ in Filippo Carlà-Uhink, Lucia Cecchet, Carlos Machado (eds), Poverty in Ancient Greece and Rome. Realities and Discourses (Routledge, London 2022) is another much more modern view of ancient towns, breaking loose from old binaries of rich and poor.

There is an old and entertaining debate on urban circus factions – for long hopelessly misinterpreted by classical historians conjuring up class, or empire-wide political alignments. Alan Cameron Circus Factions. Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium (Oxford, OUP 1976) is a classic of the genre. Supposing he was bringing order to the confusion, Cameron only added to the nonsense. Read Michael Whitby, ‘Factions, Bishops, Violence and Urban Decline’ in Jens-Uwe Krause, Christian Witschel (eds), Die Stadt in der Spatantike Niedergang oder Wandel (Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006) for something more credible, linking circus factions back to our subject.

On the complexity of Roman religion more generally, look at Stephen Mitchell and Peter Van Nuffelen (eds.), One God: Pagan Monotheism in the Roman Empire (Cambridge, CUP 2010).

Lastly, on the loss of ancient texts and their effective replacement in the 8th and 9th centuries, start with Michael Edward Moore, ‘The Ancient Fathers: Christian Antiquity, Patristics and Frankish Canon Law’ in Millennium 7 (2010), pp. 293-342. Also excellent is Markus Vinzent, Writing the History of Early Christianity. From Reception to Retrospection (Cambridge, CUP 2019). Chapter 5 on Ignatius is especially revealing.

Bernice M Kaczynski, ‘The Authority of the Fathers: Patristic Texts in Early Medieval Libraries and Scriptoria’, Journal of Medieval Latin 19 (2006), pp. 1-27 shows how the idea of the ‘church fathers’ was invented, and how the Carolingians systematically culled ancient manuscripts. A classic on the subject is Bernhard Bischoff’s chapter on the Carolingian period in his Latin Paleography. Antiquity and the Middle Ages (translated by Daibhm O. Cróinin and David Ganz, Cambridge, CUP 1990)

For vast detail on the (lack of) manuscripts surviving from before the early medieval period use www.tertullian.org. The sheer volume of information is bewildering. In direct contrast to the extraordinarily telling lack of early manuscripts. The Roman Empire we see, and the early church with it, are very largely creations of the Carolingian court and its determined campaign to justify its authority.