Loss, love and the struggle to stay alive in 1912

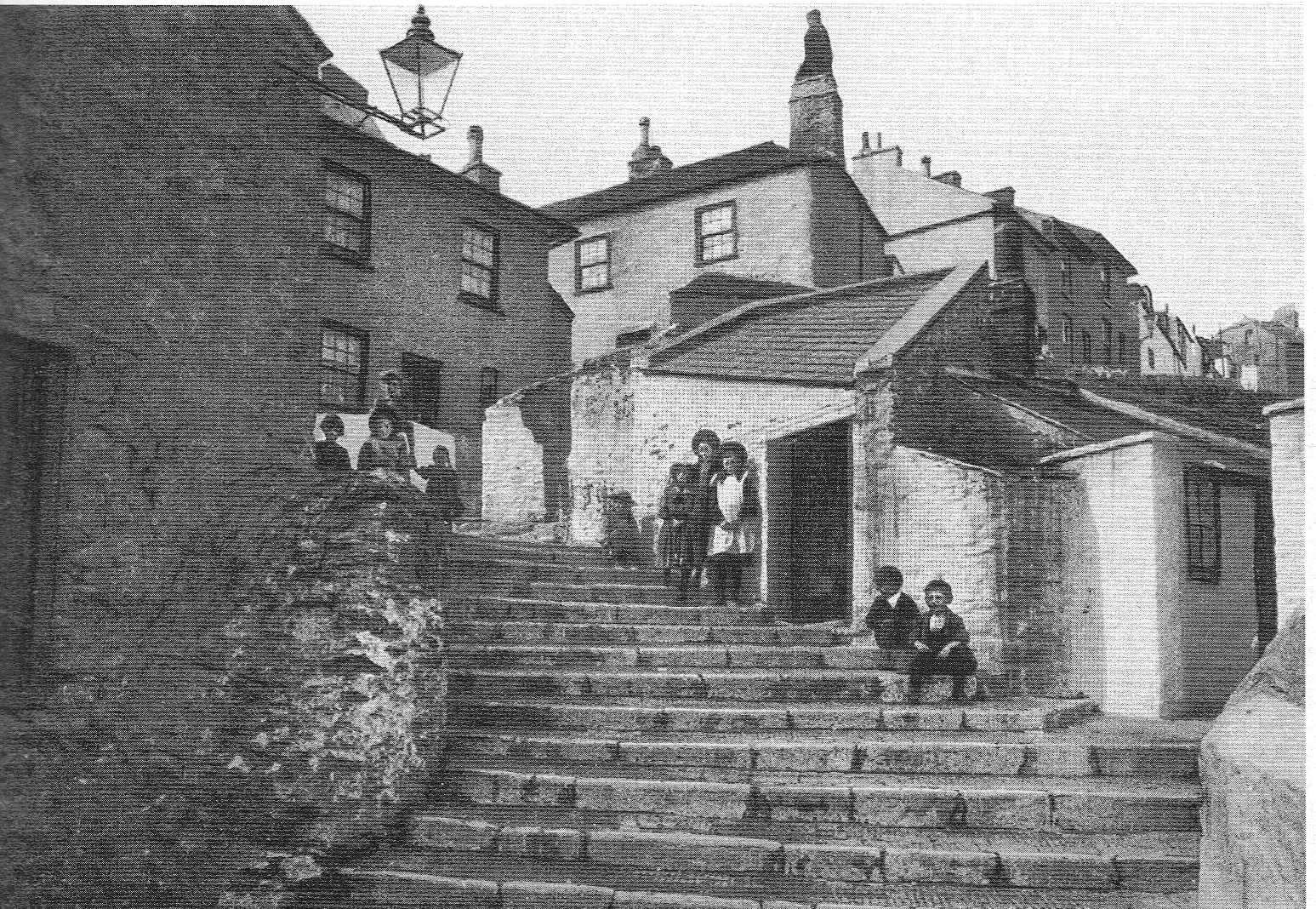

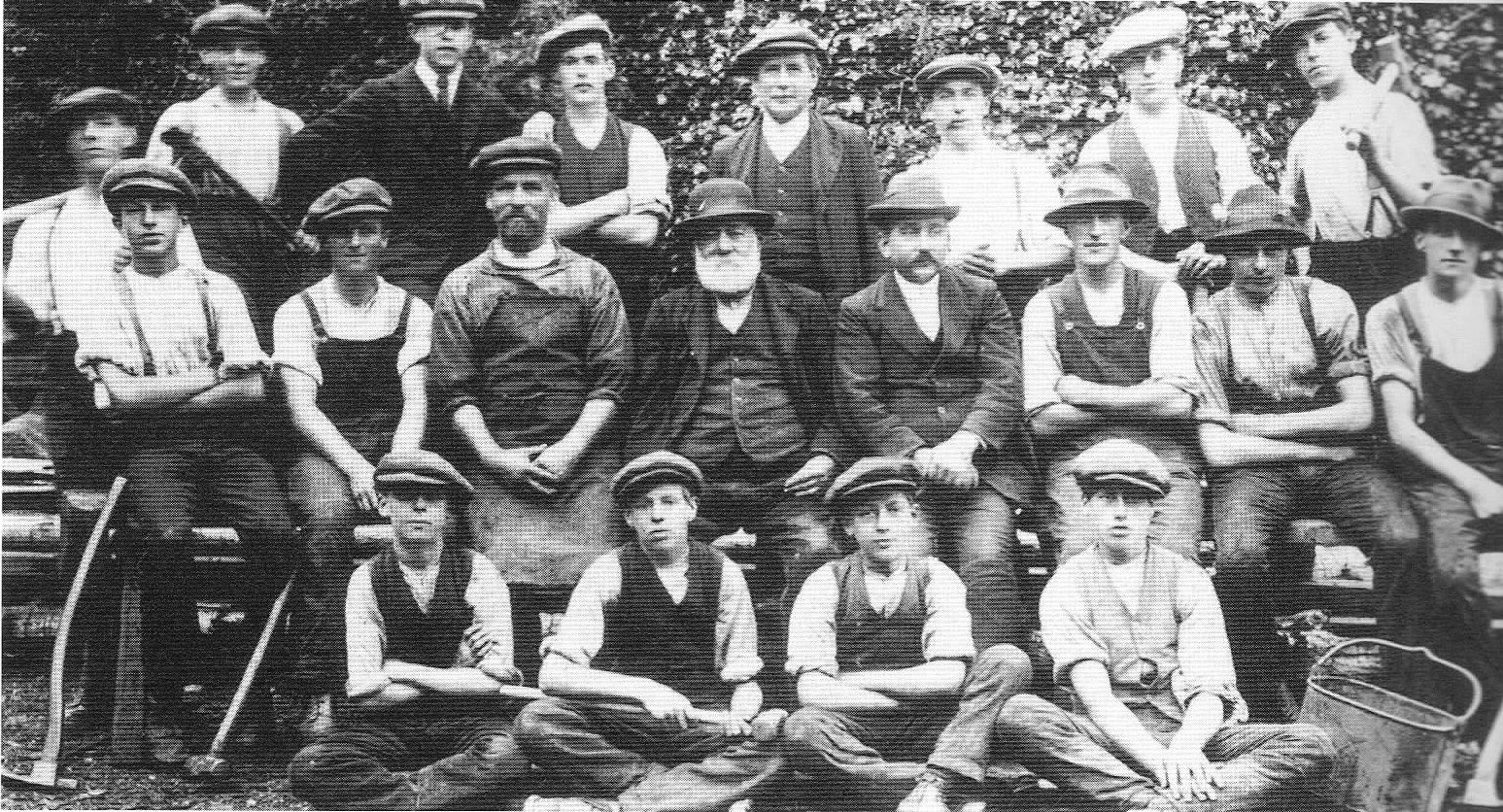

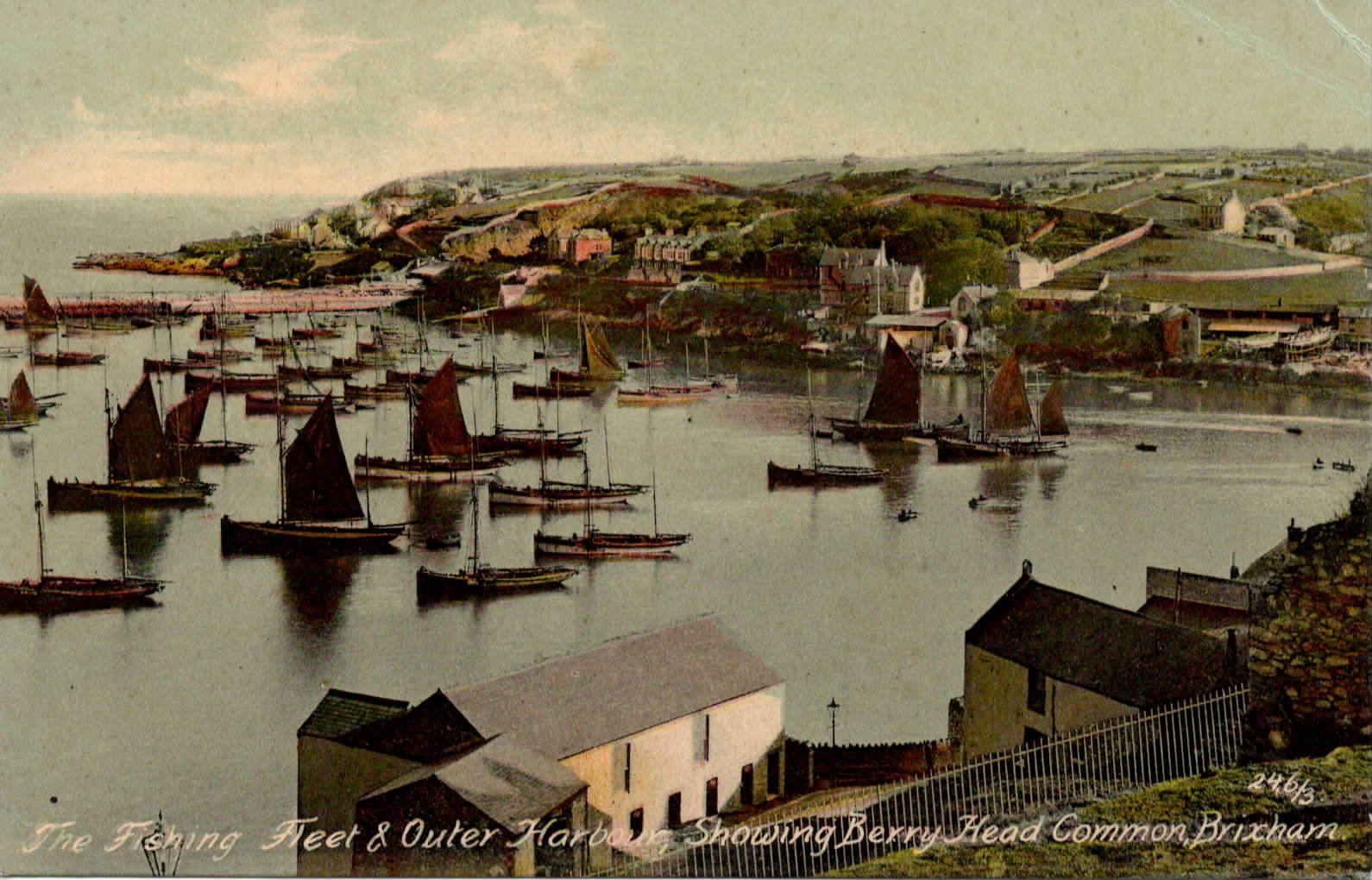

Jon explains his decision to write an historical novel, A Spring Marrying. He discovered the extraordinary history of the sail trawlers working off the English coast before 1939 whilst making a film for C4. It was the men who crewed them that fascinated him the most. Down in Brixham, Devon, they had four crew – skipper, mate, deckhand, and a cookie who was often only 12 or so. Theirs was an unremitting routine. Danger and death were never far away: it was the most dangerous job in the land. Yet they earned a reputation as supreme, quietly proud seamen, religious, brilliantly able to navigate without charts and survive just about anything. Except, maybe, falling in love with the town’s most complicated young woman.

A Spring Marrying is the new novel from Jon Rosebank, published by Devon indie, Blue Poppy

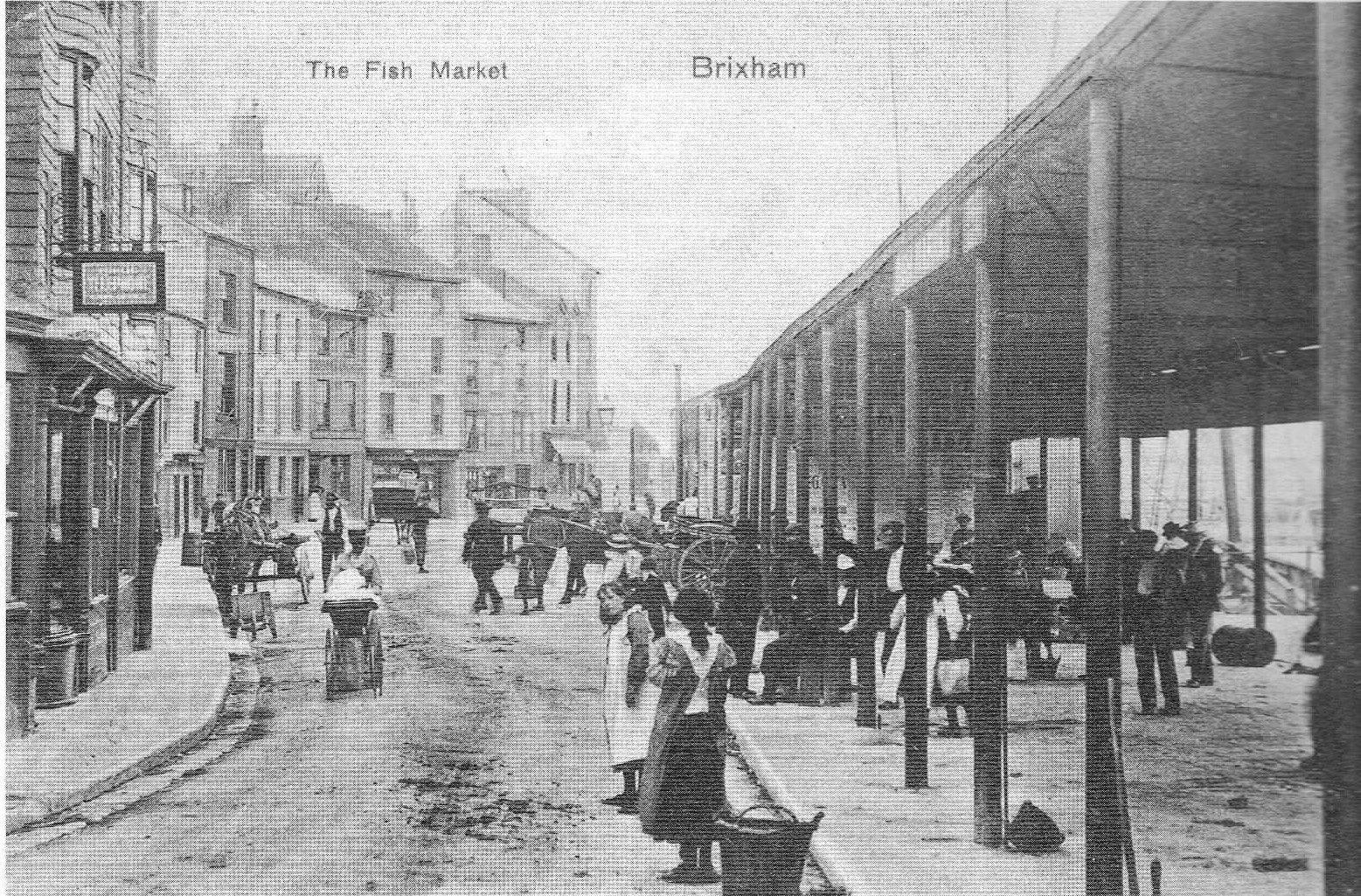

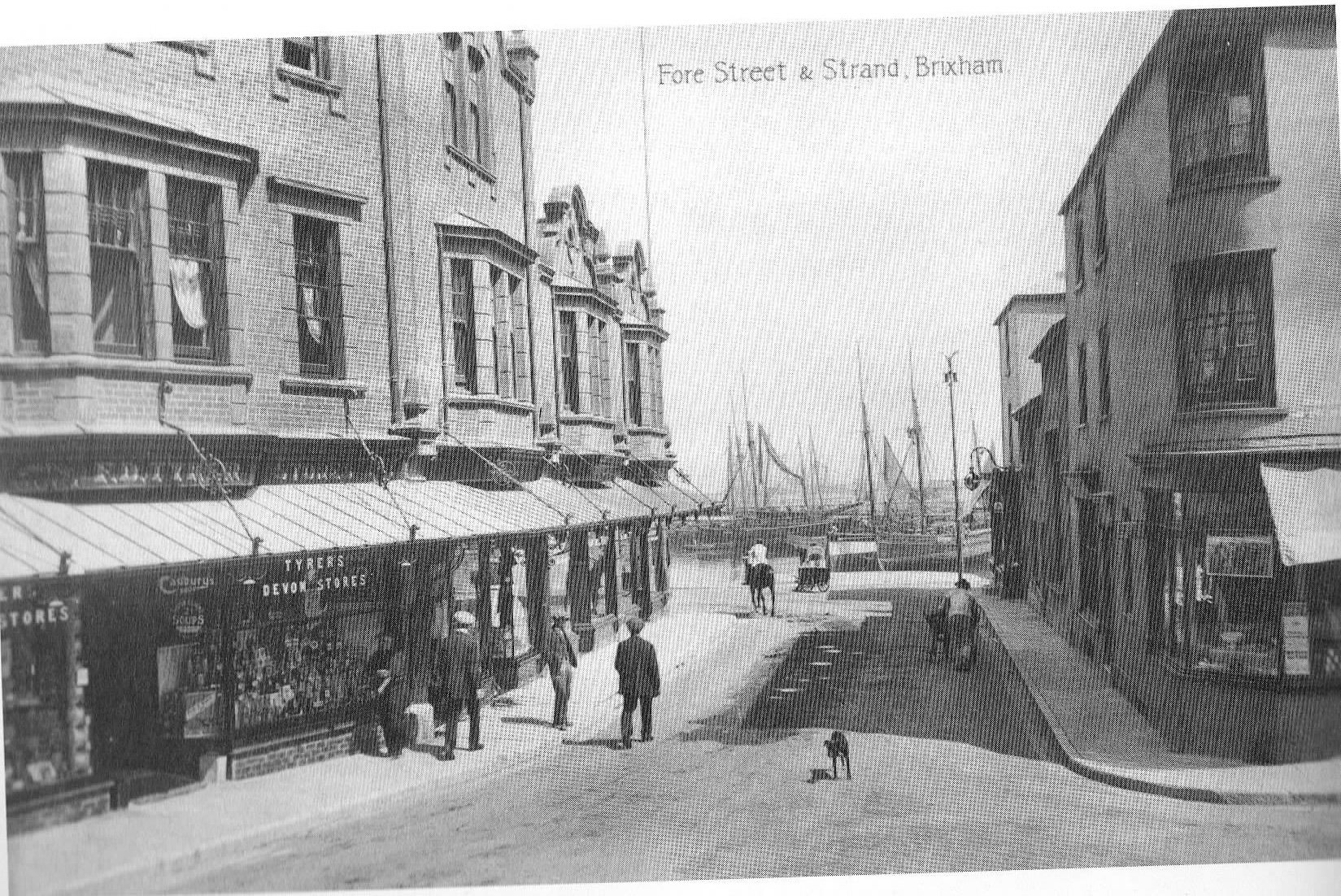

Jimmy Blackbridge is a deckhand on a sail trawler, working out of Brixham, Devon 1912-1914. He is engaged to shop-girl Alice Rogers. But Alice turns out to be far more complex a character than Jimmy at first understands. Discovering the truth draws him into the underworld of this hard-working port.

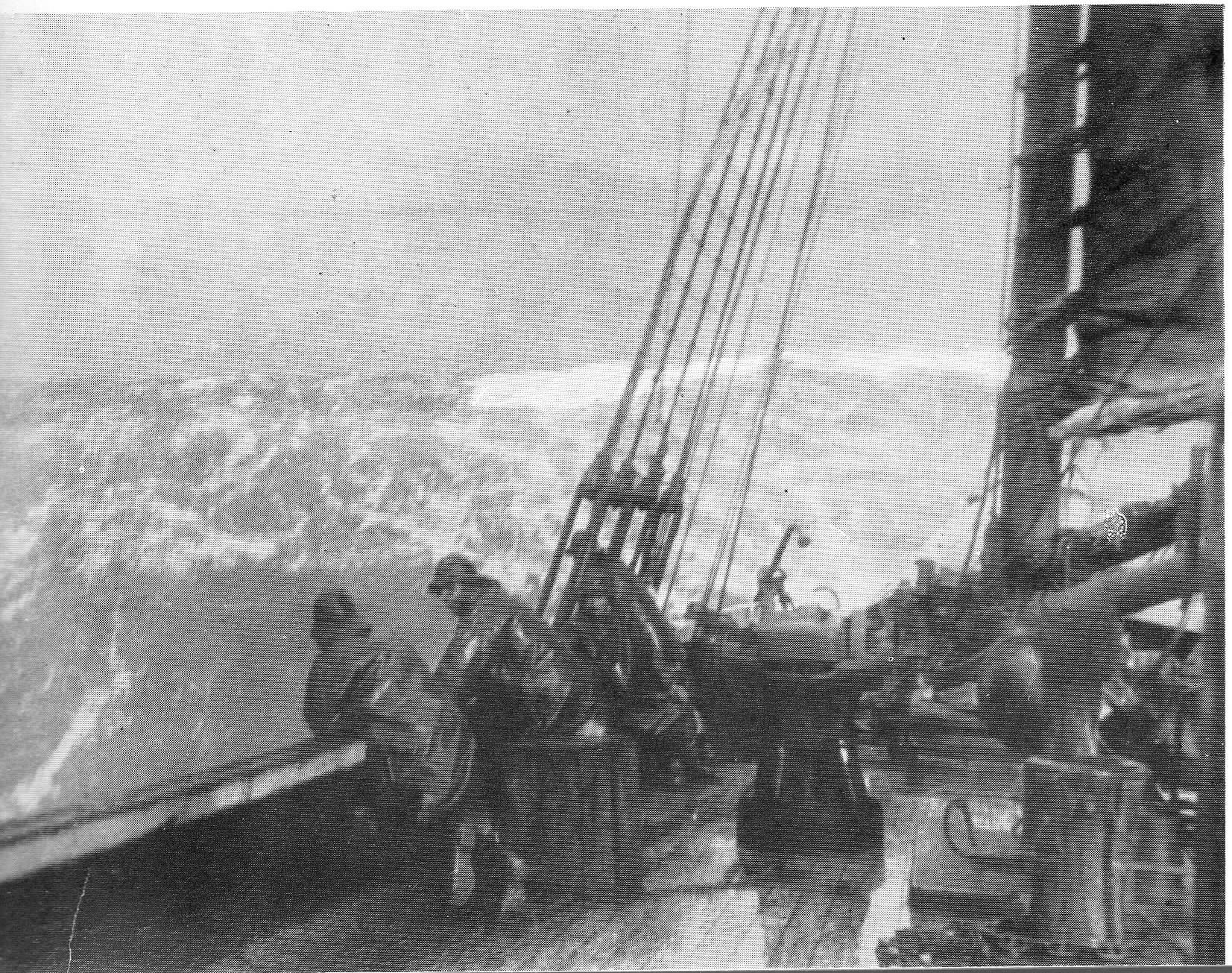

Throughout this journey, Jimmy must earn a living in the nation’s most dangerous occupation. Working the two-masted ‘smacks’ is arduous but also beautiful, a world of unrelenting labour, supreme skill and unbreakable comradeship.

‘…an historical novel that brings the past alive in human terms and in striking depth of engaging detail.’ Angela Graham, author A City Burning.

‘This novel reveals a fascinating aspect of one of the most dangerous jobs in Edwardian Britain. The book tells a tale of love kindled, found, lost, found again and then ultimately...... It is set in a supposedly innocent fishing community at Brixham, but not everything is as it seems as Jon Rosebank weaves the tale with twists that keep the reader guessing until the end. It is a thoroughly enjoyable read and once started, I didn't want to put the book down until I had finished it.’ Ian Miles

‘This novel is not just a story, it’s an experience… The imagery of a bygone era of romantic beautiful sailing ships and the hard and dangerous lives of those who sailed them is strikingly resolved. For me it is essential that the leading roles (I can so easily visualise this book as a film) are loveable. I was so sorry to say goodbye to them at the end of the book.’ Ken Edwards

Jon says:

I suppose an author might write a book like this because they are mad about boats. And it’s true that I discovered the extraordinary history of the sailing smacks when I made a film about Excelsior, a 1920s sail trawler working out of Lowestoft. I’d always found any excuse to get boats into the films I made.

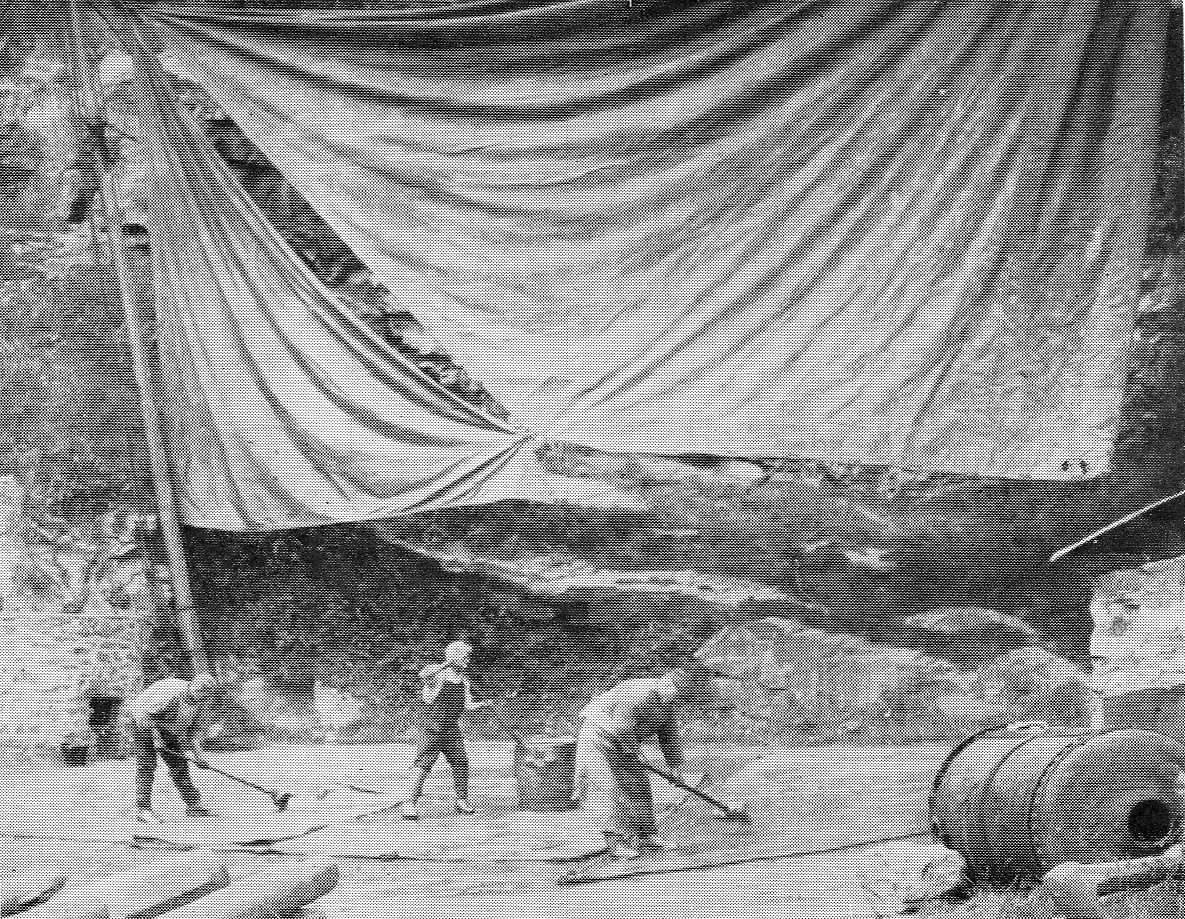

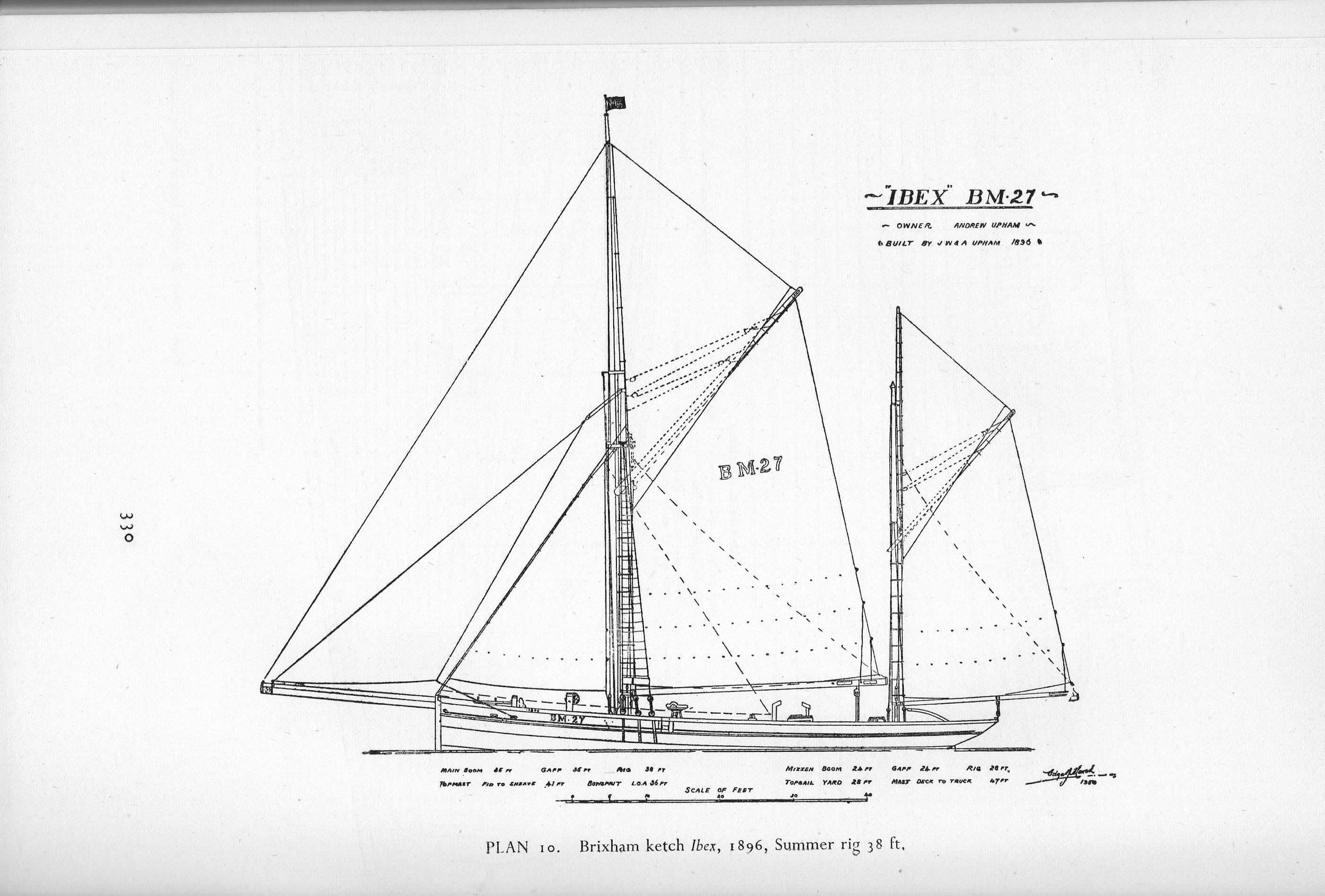

The smacks down in Brixham were gorgeous, 70-foot gaff-rigged ketches (taller mainmast, with a shorter mizzen mast further back, and two booms on each mast). They had huge ochre sails and a trawl beam with a long net they dragged along the seabed for four hours or so at a time.

But it was the men who crewed them that fascinated me. They had four crew – skipper, mate, deckhand, and a cookie who was often only 12 or so. And they were extraordinary. Theirs was an unremitting routine. Danger and death were never far away: it was the most dangerous job in the land. Yet they earned a reputation as supreme, quietly proud seamen, religious, brilliantly able to navigate without charts and survive just about anything.

And yet their life has been almost completely forgotten. History is never kind to working people and the smacksmen spoke little and wrote less. A Spring Marrying is a serious attempt to re-imagine their lives and the world of their families ashore. The Edwardian poor (alright, it’s 1912-14…) rarely appear in literature and I wanted their story to be told. I wanted their voices to be heard – not only in the poetry of the foresail halyards and the topping lift, but even (insofar as it was possible) in their own Devon dialect.

Even for an historian, the temptation was to romanticise. I can only say that, the closer I grew to the community around Excelsior, and the more I read from the time and since, the more moving I found the smacksmen’s pride in their own mastery and defiance of the odds. There really does seem to have been a profound hope and a quiet humour beating at the heart of their struggle to stay alive and to make a poor living. They were very good at what they did and they knew it.

This, then, is an historian’s recreation of life among the working poor. But having said all that, people tell me that the book is a romance and a page-turning thriller, or just a good read. And that it takes on challenging issues about relationships in a striking way. I hope you will find your own way to enjoy it.

Angela Graham’s full review

Jon Rosebank’s novel, A Spring Marrying, is bursting with nerve and verve. Nerve because we are carried through the twists and turns of the protagonist’s relationship with two potential brides in a notably confident handling of subtleties of motivation. Verve because of the convincing and buoyant rendition of both the characters’ English dialect and the nautical and trade terminology of the pre-World War One community of Devon trawlermen which is the book’s setting. There is no collision or confusion for the reader among these three threads but rather a remarkably fluid interweaving. The world of these Devonian ‘smacksmen’ and their families is realised with particular vividness because we ‘hear’ them in their own speech, and because the nautical detail is delivered in service to the writerly business of grounding us in the scene – we know where we are in the very terms used by the world we are reading about. A historical novel that brings the past alive in human terms and in striking depth of engaging detail.

Bibliography

I first encountered the smacksmen in 1998 when I made a film about the Lowestoft smack Excelsior. It was obvious that this was an extraordinary way of working life that had been lost, very nearly without trace. History has been unkind to working people and especially to those, like the smacksmen, who recorded very little. This book is an attempt to reimagine their life. Even for an historian, the temptation was to romanticise. I can only say that, the closer I grew to the community around Excelsior, and the more I read from the time and since, the more moving I found the smacksmen’s pride in their own mastery and defiance of the odds. There really does seem to have been a profound hope and a quiet humour beating at the heart of their struggle to stay alive and to make a poor living. They were very good at what they did and they knew it.

With skipper Stuart White and his team, we helped restore Excelsior to working order and finally went trawling under sail in the North Sea. There are not many alive who have had such a privilege. I had conversations about points of working a smack with Percy Thorpe, who had been a smacksman in the 1930s. I met William Finch, whose father had been a smacksman and whose book The Sea in my Blood (Diss 1992) is a detailed account of life aboard. I also worked with Robb Robinson, whose Trawling. The Rise and Fall of the British Trawl Fishery (University of Exeter 1996) is the place to go for an academic overview. The film, presented by actor Bernard Hill, went out on Channel 4 as Fish and Ships (not my choice, not least because there are other films of that name) and is now on YouTube.

Brixham smacks were slightly smaller than those that worked out of Lowestoft, and sailed with three men and a boy, rather than four. Otherwise they were almost identical and the pattern of their crews’ life the same. Edgar J March, Sailing Trawlers. The Story of Deep-Sea Fishing with Long Line and Trawl (London 1953) has been my bible, throughout the making of the film and the writing of the book. March researched his work in interviews with dozens of surviving smacksmen and he too found them uncomplaining, proud of what they had achieved. He sought out the smacks that still survived, many by then rotting in creeks. He painstakingly recorded every bolt and batten, strop and knee, down to the quarter of an inch. His book has many pages of exquisite diagrams and tables of details. It is as close to working a smack as it is possible to be without smelling the cutch and the catch.

Many local details come from the Brixham edition of the Western Guardian for these years. I also drew on the censuses and local directories. Other details come from Charles Gregory, Brixham, in Devonia (Totnes 1896), republished in 2011 by the British Library. You’ll find that a number of the events in this book – the sinking of the Empress of India for example – are based on fact. Some of the people, like Dr Francis Brett Young, I have also borrowed from history. I have cheated Brett Young’s book Deep Sea forward by a few months. Similarly, the appearance of the U-boats in the Channel. But I have tried to tell a story that could have happened.

There are a number of local publications that have been helpful. David Parker, Edwardian Devon 1900-1914. Before the Lights went Out (Stroud 2016) is as much about the period before 1900 as after, but gives helpful context. John Corin, Provident and the Story of the Brixham Smacks (Tops’l Books, Reading 1980) is a fine introduction to the smacks, though I discover we differ on some details. Other books are mainly collections of photographs, notably Ted Gosling, Brixham Revisited (Tempus, Stroud 2005) and Chips Barber, Brixham of Yesteryear (3 parts, Obelisk, Exeter 2006). They offer fleeting impressions of living in these streets. Two other books give us rare insights into this working-class world. Stephen Reynolds, Bob Woolley and Tom Woolley, Seems So! A working-class view of politics (London 1911) was written by Reynolds, a journalist and novelist, with two Sidmouth brothers with whom he lodged for many years. The Woolleys were not smacksmen, although they fished from an early motorboat. Seems So! is an invaluable source, not only for working-class views, but also of authentic Devon dialect of the period. William J Slade, Out of Appledore (London 1959) is a very rare account of life at sea, written by the skipper of small coasters trading out of a north Devon harbour from the early years of the century.

I am very grateful to the South West Maritime History Society and particularly to John Risdon of the Galmpton and Churston District Local History Group for checking the details of my narrative of life aboard. Any mistakes of course remain my own.